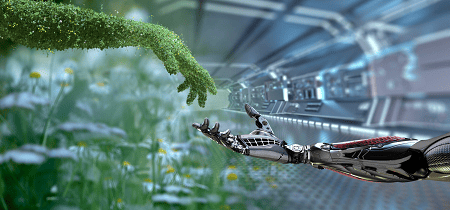

Sustainable Technology of 2990 ?

While it’s impossible to predict the future with certainty, we can explore some potential sustainable technologies that might exist in 2990 based on current trends and advancements:

Advanced Energy Solutions:

- Fusion Power: If humanity manages to achieve viable fusion power, it could become a primary energy source, providing clean and abundant energy.

- Space-Based Solar Power: Large-scale solar farms in space could beam energy back to Earth, providing a continuous and reliable source of renewable energy.

- Advanced Energy Storage: Highly efficient and compact energy storage solutions could revolutionize energy distribution and usage, making renewable energy sources more reliable.

Environmental Restoration and Conservation:

- Advanced Carbon Capture and Sequestration: Technologies that can efficiently remove carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and store it securely could play a crucial role in mitigating climate change.

- Ocean Cleanup and Restoration: Advanced robotics and biotechnology could be used to clean up pollution in the oceans and restore marine ecosystems.

- De-extinction and Biodiversity Preservation: Genetic engineering and cloning technologies could be used to bring back extinct species and preserve biodiversity.

Sustainable Resource Management:

- Circular Economy Technologies: Advanced recycling and material recovery technologies could enable a truly circular economy, minimizing waste and maximizing resource utilization.

- Vertical Farming and Controlled Environment Agriculture: Indoor farming systems that use minimal resources and can be located in urban areas could become a major source of food production.

- Water Purification and Desalination: Advanced filtration and desalination technologies could provide access to clean water in even the most arid regions.

Other Potential Technologies:

- Advanced Materials: New materials with unique properties, such as self-healing materials or materials that can adapt to their environment, could revolutionize various industries.

- Artificial Intelligence and Automation: AI and robotics could be used to optimize resource usage, automate sustainable practices, and even manage entire ecosystems.

- Biotechnology: Advancements in genetic engineering and synthetic biology could lead to new ways of producing sustainable materials, fuels, and even medicines.

Important Considerations:

- Ethical Implications: As with any technology, it’s crucial to consider the ethical implications of these advancements and ensure they are used responsibly.

- Accessibility: Sustainable technologies should be accessible to everyone, regardless of their location or socioeconomic status.

- Resilience: Sustainable systems should be designed to be resilient to natural disasters and other unforeseen events.

It’s important to remember that this is just a speculative look at the future. The actual technologies that exist in 2990 could be very different from what we imagine today. However, by focusing on sustainability and responsible innovation, we can increase the chances of creating a future where technology helps us live in harmony with the planet.Sources and related content

What is Sustainable Technology of 2990 ?

It’s fascinating to imagine what sustainable technology might look like in 2990! While we can’t predict the future with certainty, here are some ideas based on current trends and advancements:

Advanced Energy Solutions:

- Fusion Power: If humanity manages to achieve viable fusion power, it could become a primary energy source, providing clean and abundant energy.

- Space-Based Solar Power: Large-scale solar farms in space could beam energy back to Earth, providing a continuous and reliable source of renewable energy.

- Advanced Energy Storage: Highly efficient and compact energy storage solutions could revolutionize energy distribution and usage, making renewable energy sources more reliable.

Environmental Restoration and Conservation:

- Advanced Carbon Capture and Sequestration: Technologies that can efficiently remove carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and store it securely could play a crucial role in mitigating climate change.

- Ocean Cleanup and Restoration: Advanced robotics and biotechnology could be used to clean up pollution in the oceans and restore marine ecosystems.

- De-extinction and Biodiversity Preservation: Genetic engineering and cloning technologies could be used to bring back extinct species and preserve biodiversity.

Sustainable Resource Management:

- Circular Economy Technologies: Advanced recycling and material recovery technologies could enable a truly circular economy, minimizing waste and maximizing resource utilization.

- Vertical Farming and Controlled Environment Agriculture: Indoor farming systems that use minimal resources and can be located in urban areas could become a major source of food production.

- Water Purification and Desalination: Advanced filtration and desalination technologies could provide access to clean water in even the most arid regions.

Other Potential Technologies:

- Advanced Materials: New materials with unique properties, such as self-healing materials or materials that can adapt to their environment, could revolutionize various industries.

- Artificial Intelligence and Automation: AI and robotics could be used to optimize resource usage, automate sustainable practices, and even manage entire ecosystems.

- Biotechnology: Advancements in genetic engineering and synthetic biology could lead to new ways of producing sustainable materials, fuels, and even medicines.

Important Considerations:

- Ethical Implications: As with any technology, it’s crucial to consider the ethical implications of these advancements and ensure they are used responsibly.

- Accessibility: Sustainable technologies should be accessible to everyone, regardless of their location or socioeconomic status.

- Resilience: Sustainable systems should be designed to be resilient to natural disasters and other unforeseen events.

It’s important to remember that this is just a speculative look at the future. The actual technologies that exist in 2990 could be very different from what we imagine today. However, by focusing on sustainability and responsible innovation, we can increase the chances of creating a future where technology helps us live in harmony with the planet.Sources and related content

Who is required Sustainable Technology of 2990 ?

It’s a great question to consider who would need sustainable technology in 2990! Here’s a breakdown of potential beneficiaries:

- Humanity as a whole: This is the most obvious answer. Sustainable technology would be essential for ensuring the long-term survival and well-being of human civilization. This includes access to clean energy, clean water, food, and a habitable environment.

- Future generations: Those living in 2990 and beyond would inherit the consequences of decisions made today. Sustainable technology would be crucial for ensuring they have a healthy planet and access to the resources they need.

- Ecosystems and biodiversity: Sustainable technology would play a vital role in protecting and restoring ecosystems, preserving biodiversity, and mitigating the impacts of climate change.

- Other species: Many other species on Earth would benefit from sustainable technology that helps protect their habitats and ensures their survival.

- Potentially, even off-world colonies: If humanity has expanded beyond Earth by 2990, sustainable technologies would be even more critical for establishing and maintaining self-sufficient colonies in space or on other planets.

In essence, sustainable technology in 2990 would be needed by anyone and anything that relies on a healthy planet and its resources. This includes all living beings and the complex systems that support them.

It’s important to remember that the need for sustainable technology is not just about solving current problems, but also about preventing future ones. By investing in sustainable solutions today, we can help ensure a better future for all.

When is required Sustainable Technology of 2990 ?

That’s a really interesting question! It’s not just about who needs sustainable technology in 2990, but also when it’s needed. Here’s how I see it:

- Continuously, from now until 2990 and beyond: Sustainable technology isn’t a one-time solution. It’s an ongoing process of developing and implementing technologies that minimize our impact on the planet. So, the need for sustainable technology starts now and continues indefinitely.

- Proactively, to prevent future problems: We need to be developing and implementing sustainable technology now to prevent the problems of the future. This includes things like mitigating climate change, preserving biodiversity, and ensuring access to clean resources.

- Adaptively, to respond to changing conditions: The environment and our needs are constantly changing. Sustainable technology needs to be adaptable to these changes, allowing us to respond to new challenges and ensure long-term sustainability.

- Urgently, to address current crises: We’re already facing many environmental challenges, such as climate change, pollution, and resource depletion. Sustainable technology is urgently needed to address these crises and prevent them from worsening.

In short, the need for sustainable technology is constant, proactive, adaptive, and urgent. It’s not just about the year 2990, but about every year leading up to it and beyond. By prioritizing sustainable technology now, we can help create a better future for all.Sources and related content

COURTESY : Accenture

Where is required Sustainable Technology of 2990 ?

The need for sustainable technology in 2990 (and, of course, long before then) isn’t confined to a single place. It’s a global and even potentially extraterrestrial concern. Here’s a breakdown:

- Everywhere on Earth: This is the most obvious answer. Every region of the planet, from bustling cities to remote wilderness areas, will require sustainable technologies to address local and global environmental challenges. This includes:

- Urban centers: Sustainable urban planning, green buildings, efficient transportation, and waste management will be crucial.

- Rural areas: Sustainable agriculture, water management, and renewable energy solutions will be necessary.

- Oceans: Technologies for cleaning up pollution, protecting marine ecosystems, and managing fisheries sustainably will be vital.

- Atmosphere: Technologies for carbon capture, air pollution reduction, and climate change mitigation will be essential.

- Potentially beyond Earth: If humanity has expanded beyond Earth by 2990, the need for sustainable technology will extend to:

- Space habitats: Closed-loop life support systems, resource utilization, and energy production will be critical for off-world colonies.

- Other planets or moons: If resources are being extracted from other celestial bodies, it will need to be done sustainably to minimize environmental impact.

- “Cyberspace” or the digital realm: While not a physical location, the digital world also has an environmental footprint. Sustainable technology will be needed to make computing and communication systems more energy efficient and to manage the environmental impact of data centers and electronic waste.

In essence, sustainable technology in 2990 will be required wherever human activity takes place, whether it’s on Earth or beyond. The interconnectedness of global systems means that even seemingly isolated actions can have far-reaching consequences. Therefore, a global, and potentially even interplanetary, approach to sustainable technology will be essential.Sources and related content

How is required Sustainable Technology of 2990 ?

It’s not just about where sustainable technology is needed in 2990, but also how it will be implemented and integrated into society. Here are some key aspects:

- Globally integrated systems: Sustainable technologies will need to be interconnected and integrated on a global scale to address global challenges like climate change and resource management. This will require international cooperation and data sharing.

- Localized solutions: While global integration is important, sustainable technologies will also need to be adapted to local contexts and needs. This means considering the specific environmental, social, and economic conditions of different regions.

- Embedded in infrastructure: Sustainable technologies will likely be deeply embedded in the infrastructure of 2990, from energy grids and transportation systems to buildings and communication networks. This will require careful planning and design.

- Driven by artificial intelligence: AI could play a significant role in optimizing and managing sustainable technologies. AI systems could monitor resource usage, predict environmental changes, and automate sustainable practices.

- Accessible and equitable: It’s crucial that sustainable technologies are accessible and affordable for everyone, regardless of their location or socioeconomic status. This will require addressing issues of equity and social justice.

- Resilient and adaptable: Sustainable systems need to be designed to be resilient to natural disasters, climate change impacts, and other unforeseen events. They should also be adaptable to changing conditions and new challenges.

- Ethically developed and used: It’s essential to ensure that sustainable technologies are developed and used ethically, considering their potential impacts on society and the environment. This will require careful consideration of ethical guidelines and regulations.

In essence, sustainable technology in 2990 will need to be seamlessly integrated into all aspects of life, from the global to the local level, while being ethically developed, accessible, resilient, and adaptable. It will be a complex and interconnected system that supports a sustainable future for all.Sources and related content

Case study is Sustainable Technology of 2990 ?

It’s impossible to provide a real case study of sustainable technology in 2990, as that’s a thousand years in the future! However, we can create a hypothetical case study based on current trends and projections, which can be a useful exercise in imagining potential futures.

Hypothetical Case Study: The Great Lakes Restoration Project, 2990

Background: By the late 21st century, the Great Lakes ecosystem had suffered severe degradation due to pollution, invasive species, and climate change. Traditional methods of restoration proved insufficient.

The 2990 Solution: A multi-faceted, technologically advanced approach was implemented, combining several key sustainable technologies:

- AI-Powered Ecosystem Management: A vast network of sensors and AI systems constantly monitored the health of the Great Lakes ecosystem, including water quality, biodiversity, and invasive species populations. The AI could predict potential problems and automatically deploy targeted interventions, such as releasing native species or removing pollutants.

- Nano-Filtration and Remediation: Nanotechnology was used to develop highly efficient filters that could remove microplastics, heavy metals, and other pollutants from the water. Self-replicating nanobots were deployed to break down harmful chemicals and restore contaminated sediments.

- Bioengineered Restoration: Genetically engineered microbes were used to break down invasive species and restore native plant and animal populations. Synthetic biology was also used to create artificial reefs and wetlands, providing habitat for aquatic life.

- Atmospheric Carbon Capture and Geoengineering: Large-scale carbon capture facilities removed CO2 from the atmosphere, mitigating the effects of climate change on the Great Lakes. Stratospheric aerosol injection (a form of geoengineering) was used cautiously to manage regional temperatures and precipitation patterns.

- Circular Economy Integration: All restoration efforts were integrated with a circular economy framework. Waste materials from the cleanup process were recycled and reused, minimizing the environmental impact of the project.

Results: By 2990, the Great Lakes ecosystem had been largely restored. Water quality was excellent, native species thrived, and invasive species were under control. The AI-powered management system ensured the long-term health and resilience of the ecosystem. The project served as a model for ecosystem restoration around the world.

Lessons Learned (Hypothetically):

- Integrated, multi-technology solutions are essential for addressing complex environmental challenges.

- AI and nanotechnology can play crucial roles in environmental restoration and management.

- A circular economy approach is crucial for minimizing environmental impact.

- International cooperation is essential for addressing global environmental problems.

Limitations: This is a highly speculative scenario. The actual technologies available in 2990 could be very different. Furthermore, predicting the social and political context of that era is impossible.

This hypothetical case study is meant to be an exercise in imagining the possibilities, not a prediction of the future. However, it highlights the potential of sustainable technology to address environmental challenges and create a more sustainable future

.COURTESY : RBC

White paper on Sustainable Technology of 2990 ?

White Paper: Sustainable Technology in 2990: A Vision for a Thriving Future

Abstract:

This white paper explores potential advancements in sustainable technology by the year 2990. It acknowledges the inherent limitations of predicting the future but aims to stimulate thought and discussion about the long-term trajectory of technological development and its crucial role in ensuring a sustainable future for humanity and the planet. The paper examines potential breakthroughs in energy, resource management, environmental restoration, and other key areas, while also considering the ethical and societal implications of such advancements.

1. Introduction:

The 29th century presents a vast expanse of time for technological innovation. While predicting specific technologies is futile, we can extrapolate from current trends and imagine potential pathways toward a truly sustainable future. This paper focuses on the kinds of technologies that might be essential for a thriving civilization in 2990, emphasizing the interconnectedness of technological, environmental, and societal factors.

2. Advanced Energy Solutions:

The cornerstone of any sustainable future is clean, abundant energy. By 2990, several possibilities could have become realities:

- Fusion Power: Controlled nuclear fusion, if achieved, could provide a virtually limitless supply of clean energy.

- Space-Based Solar Power: Large-scale solar arrays in orbit could capture solar energy continuously and beam it back to Earth.

- Advanced Energy Storage: Highly efficient and compact energy storage technologies would be essential for balancing intermittent renewable sources and enabling decentralized energy systems.

- Geothermal Energy: Enhanced geothermal systems could tap into the Earth’s vast heat resources for clean energy.

3. Sustainable Resource Management:

A circular economy, minimizing waste and maximizing resource utilization, would be paramount:

- Advanced Recycling and Material Recovery: Technologies capable of efficiently separating and reprocessing materials at the molecular level would enable near-total recycling.

- Biomanufacturing: Using biological systems to produce materials and products could reduce reliance on fossil fuels and other finite resources.

- Precision Agriculture: Advanced sensors, AI, and robotics could optimize agricultural practices, minimizing water and fertilizer use while maximizing yields.

- Vertical Farming and Controlled Environment Agriculture: Indoor farming systems could produce food locally, reducing transportation costs and environmental impact.

4. Environmental Restoration and Conservation:

Reversing environmental damage and preserving biodiversity would be critical:

- Advanced Carbon Capture and Sequestration: Technologies capable of efficiently removing CO2 from the atmosphere and oceans would be crucial for mitigating climate change.

- Ecosystem Restoration: Biotechnology and ecological engineering could be used to restore damaged ecosystems and create artificial habitats.

- De-extinction and Biodiversity Preservation: Genetic engineering and cloning technologies could be used to bring back extinct species and preserve genetic diversity.

- Ocean Cleanup and Management: Advanced robotics and biotechnology could be used to remove pollution and manage marine ecosystems sustainably.

5. Other Key Technologies:

- Advanced Materials: Self-healing materials, adaptive materials, and other advanced materials could revolutionize various industries, reducing waste and improving efficiency.

- Artificial Intelligence and Automation: AI and robotics could be used to optimize resource usage, automate sustainable practices, and manage complex environmental systems.

- Biotechnology: Advancements in genetic engineering, synthetic biology, and other biotechnologies could lead to new ways of producing sustainable materials, fuels, and medicines.

6. Ethical and Societal Considerations:

Technological advancements must be guided by ethical principles:

- Equity and Accessibility: Sustainable technologies must be accessible to everyone, regardless of their location or socioeconomic status.

- Environmental Justice: The benefits and burdens of technological development must be distributed fairly.

- Responsible Innovation: New technologies must be developed and used responsibly, considering their potential impacts on society and the environment.

- Global Cooperation: Addressing global challenges like climate change and resource depletion requires international cooperation and shared responsibility.

7. Conclusion:

The vision presented in this white paper is ambitious but achievable. By prioritizing sustainable technology and embracing responsible innovation, humanity can create a thriving future for itself and the planet. Continued research, development, and collaboration are essential to realizing this vision and ensuring a sustainable future for generations to come. The journey to 2990 begins now.

Industrial application of Sustainable Technology of 2990 ?

It’s fascinating to imagine the industrial applications of sustainable technology in 2990! Here are some possibilities, building on current trends and potential future breakthroughs:

1. Advanced Manufacturing and Production:

- Circular Economy Factories: Factories of the future could operate on closed-loop systems, where all materials are continuously recycled and reused. Advanced robotics and AI would manage the flow of materials, ensuring minimal waste and maximum efficiency.

- Biomanufacturing: Industries could utilize biological systems to produce a wide range of products, from materials and chemicals to pharmaceuticals and even electronics. This would reduce reliance on fossil fuels and other finite resources.

- Additive Manufacturing (4D Printing): 4D printing, where objects can change shape over time in response to stimuli, could revolutionize manufacturing. Products could be designed to adapt to their environment or to self-assemble, reducing waste and enabling customized production.

2. Energy and Infrastructure:

- Smart Grids and Decentralized Energy Systems: Energy grids could be highly intelligent, optimizing energy distribution and integrating various renewable energy sources. Decentralized energy systems, powered by local renewable resources, could become more common, increasing resilience and reducing transmission losses.

- Sustainable Transportation: Industries could rely on advanced transportation systems powered by clean energy sources. This could include high-speed rail networks, electric vehicles, and even advanced air mobility systems.

- Green Buildings and Infrastructure: Buildings could be self-sufficient, generating their own energy and managing their own resources. Advanced materials and AI could be used to create buildings that adapt to their environment, minimizing energy consumption and maximizing occupant comfort.

3. Resource Extraction and Processing:

- Sustainable Mining: Mining operations could utilize advanced robotics and AI to extract resources with minimal environmental impact. New technologies could be developed to extract valuable materials from waste and byproducts, reducing the need for traditional mining.

- Ocean Mining (Sustainable): If ocean mining is necessary, it could be done with advanced, AI-controlled submersibles that minimize disruption to marine ecosystems.

- Water Purification and Desalination: Industries could have access to highly efficient water purification and desalination technologies, ensuring a sustainable supply of clean water even in arid regions.

4. Agriculture and Food Production:

- Vertical Farms and Controlled Environment Agriculture: Large-scale vertical farms and controlled environment agriculture facilities could be located in urban areas, providing fresh produce locally and reducing transportation costs and environmental impact.

- Precision Agriculture: AI and robotics could be used to optimize agricultural practices, minimizing water and fertilizer use while maximizing yields.

- Sustainable Aquaculture: Advanced aquaculture systems could be developed to produce seafood sustainably, reducing pressure on wild fish populations.

5. Environmental Remediation and Restoration:

- Advanced Carbon Capture and Sequestration: Industries could utilize advanced carbon capture technologies to remove CO2 from their emissions, mitigating the effects of climate change.

- Ecosystem Restoration: Industries could play a role in restoring damaged ecosystems, using biotechnology and ecological engineering to repair environmental damage.

Important Considerations:

- AI and Automation: AI and robotics would likely play a significant role in optimizing and managing sustainable technologies across all industries.

- Data and Connectivity: Advanced sensor networks and communication systems would be essential for monitoring and managing sustainable systems.

- Collaboration and Knowledge Sharing: Industries would need to collaborate and share knowledge to develop and implement sustainable technologies effectively.

It’s crucial to remember that these are just potential scenarios. The actual industrial applications of sustainable technology in 2990 could be very different. However, by focusing on sustainability and responsible innovation, we can increase the chances of creating a future where technology helps us live in harmony with the planet.Sources and related content

Research and development of Sustainable Technology of 2990 ?

It’s exciting to think about the research and development (R&D) that might lead to sustainable technology in 2990! Here’s a breakdown of potential areas of focus, keeping in mind that this is speculative:

1. Fundamental Science:

- New Physics: Exploring and harnessing new fundamental forces or particles could unlock entirely new forms of energy production and manipulation of matter.

- Consciousness and AI: Understanding consciousness could lead to more efficient and ethical AI systems that can better manage complex sustainable systems.

- Quantum Biology: Investigating the intersection of quantum mechanics and biology could reveal new ways to manipulate biological systems for sustainable purposes, like enhanced photosynthesis or bioremediation.

2. Materials Science:

- Self-Healing and Adaptive Materials: Developing materials that can repair themselves or adapt to their environment could revolutionize infrastructure, reducing waste and increasing longevity.

- Programmable Matter: Researching matter that can be programmed to change its properties on demand could lead to revolutionary manufacturing and resource management techniques.

- Exotic Materials: Exploring and utilizing materials with extraordinary properties, like superconductors at room temperature or materials with negative mass, could open up new possibilities for sustainable technologies.

3. Energy:

- Fusion Breakthroughs: Continued research into fusion energy, including alternative confinement methods and fuel cycles, could finally make it a viable and widespread energy source.

- Space-Based Energy Transmission: Developing efficient and safe methods for transmitting energy from space-based solar arrays could provide a continuous and abundant source of clean energy.

- Advanced Energy Storage: Researching new battery chemistries, supercapacitors, and other energy storage technologies could lead to highly efficient and compact energy storage solutions.

4. Biotechnology:

- Synthetic Biology: Engineering new biological systems for sustainable purposes, such as producing biofuels, breaking down pollutants, or even creating new materials.

- Genetic Engineering: Developing precise and ethical gene editing techniques could be used to enhance agricultural productivity, restore ecosystems, and even cure diseases.

- Bioremediation: Engineering microbes to clean up pollution and restore contaminated environments could provide a sustainable solution to environmental remediation.

5. Artificial Intelligence and Robotics:

- AI for Ecosystem Management: Developing AI systems that can monitor, predict, and manage complex ecosystems could help preserve biodiversity and prevent environmental disasters.

- Robotics for Sustainable Practices: Creating robots that can automate sustainable practices, such as recycling, waste management, and environmental monitoring, could improve efficiency and reduce human labor.

- AI-Driven Materials Discovery: Using AI to accelerate the discovery of new materials with desired properties could lead to breakthroughs in sustainable materials science.

6. Social Sciences and Ethics:

- Sustainable Behavior: Researching how to promote sustainable behavior and encourage the adoption of sustainable technologies.

- Ethical Frameworks for Technology: Developing ethical guidelines and regulations for the development and use of advanced technologies, ensuring they are used responsibly and for the benefit of all.

- Global Governance for Sustainability: Exploring new models of global governance that can effectively address global challenges like climate change and resource depletion.

Important Considerations:

- Interdisciplinary Collaboration: R&D for sustainable technology in 2990 will require collaboration across many disciplines, including science, engineering, social sciences, and ethics.

- Long-Term Vision: Sustainable technology R&D requires a long-term vision and a commitment to investing in fundamental science, even if the immediate applications are not clear.

- Open Access and Knowledge Sharing: Sharing research findings and knowledge openly can accelerate the development and deployment of sustainable technologies.

By focusing on these areas of R&D, we can increase the chances of creating a future where sustainable technology helps us live in harmony with the planet.

COURTESY : Trending Tech

References

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Purvis, Ben; Mao, Yong; Robinson, Darren (2019). “Three pillars of sustainability: in search of conceptual origins”. Sustainability Science. 14 (3): 681–695. Bibcode:2019SuSc…14..681P. doi:10.1007/s11625-018-0627-5. ISSN 1862-4065. Text was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e Ramsey, Jeffry L. (2015). “On Not Defining Sustainability”. Journal of Agricultural and Environmental Ethics. 28 (6): 1075–1087. Bibcode:2015JAEE…28.1075R. doi:10.1007/s10806-015-9578-3. ISSN 1187-7863. S2CID 146790960.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f Kotzé, Louis J.; Kim, Rakhyun E.; Burdon, Peter; du Toit, Louise; Glass, Lisa-Maria; Kashwan, Prakash; Liverman, Diana; Montesano, Francesco S.; Rantala, Salla (2022). “Planetary Integrity”. In Sénit, Carole-Anne; Biermann, Frank; Hickmann, Thomas (eds.). The Political Impact of the Sustainable Development Goals: Transforming Governance Through Global Goals?. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 140–171. doi:10.1017/9781009082945.007. ISBN 978-1-316-51429-0.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f Bosselmann, Klaus (2010). “Losing the Forest for the Trees: Environmental Reductionism in the Law”. Sustainability. 2 (8): 2424–2448. doi:10.3390/su2082424. hdl:10535/6499. ISSN 2071-1050. Text was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 International License

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u Berg, Christian (2020). Sustainable action: overcoming the barriers. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-429-57873-1. OCLC 1124780147.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c “Sustainability”. Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 31 March 2022.

- ^ “Sustainable Development”. UNESCO. 3 August 2015. Retrieved 20 January 2022.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Kuhlman, Tom; Farrington, John (2010). “What is Sustainability?”. Sustainability. 2 (11): 3436–3448. doi:10.3390/su2113436. ISSN 2071-1050.

- ^ Nelson, Anitra (31 January 2024). “Degrowth as a Concept and Practice: Introduction”. The Commons Social Change Library. Retrieved 23 February 2024.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d UNEP (2011) Decoupling natural resource use and environmental impacts from economic growth, A Report of the Working Group on Decoupling to the International Resource Panel. Fischer-Kowalski, M., Swilling, M., von Weizsäcker, E.U., Ren, Y., Moriguchi, Y., Crane, W., Krausmann, F., Eisenmenger, N., Giljum, S., Hennicke, P., Romero Lankao, P., Siriban Manalang, A., Sewerin, S.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Vadén, T.; Lähde, V.; Majava, A.; Järvensivu, P.; Toivanen, T.; Hakala, E.; Eronen, J.T. (2020). “Decoupling for ecological sustainability: A categorisation and review of research literature”. Environmental Science & Policy. 112: 236–244. Bibcode:2020ESPol.112..236V. doi:10.1016/j.envsci.2020.06.016. PMC 7330600. PMID 32834777.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d Parrique T., Barth J., Briens F., C. Kerschner, Kraus-Polk A., Kuokkanen A., Spangenberg J.H., 2019. Decoupling debunked: Evidence and arguments against green growth as a sole strategy for sustainability. European Environmental Bureau.

- ^ Parrique, T., Barth, J., Briens, F., Kerschner, C., Kraus-Polk, A., Kuokkanen, A., & Spangenberg, J. H. (2019). Decoupling debunked. Evidence and arguments against green growth as a sole strategy for sustainability. A study edited by the European Environment Bureau EEB.

- ^ Hardyment, Richard (2024). Measuring Good Business: Making Sense of Environmental, Social & Governance Data. Abingdon: Routledge. ISBN 9781032601199.

- ^ Bell, Simon; Morse, Stephen (2012). Sustainability Indicators: Measuring the Immeasurable?. Abington: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-84407-299-6.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Howes, Michael; Wortley, Liana; Potts, Ruth; Dedekorkut-Howes, Aysin; Serrao-Neumann, Silvia; Davidson, Julie; Smith, Timothy; Nunn, Patrick (2017). “Environmental Sustainability: A Case of Policy Implementation Failure?”. Sustainability. 9 (2): 165. doi:10.3390/su9020165. hdl:10453/90953. ISSN 2071-1050.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Kinsley, M. and Lovins, L.H. (September 1997). “Paying for Growth, Prospering from Development.” Archived 17 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 15 June 2009.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Sustainable Shrinkage: Envisioning a Smaller, Stronger Economy Archived 11 April 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Thesolutionsjournal.com. Retrieved 13 March 2016.

- ^ Apetrei, Cristina I.; Caniglia, Guido; von Wehrden, Henrik; Lang, Daniel J. (1 May 2021). “Just another buzzword? A systematic literature review of knowledge-related concepts in sustainability science”. Global Environmental Change. 68: 102222. Bibcode:2021GEC….6802222A. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2021.102222. ISSN 0959-3780.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Benson, Melinda Harm; Craig, Robin Kundis (2014). “End of Sustainability”. Society & Natural Resources. 27 (7): 777–782. Bibcode:2014SNatR..27..777B. doi:10.1080/08941920.2014.901467. ISSN 0894-1920. S2CID 67783261.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Stockholm+50: Unlocking a Better Future. Stockholm Environment Institute (Report). 18 May 2022. doi:10.51414/sei2022.011. S2CID 248881465.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Scoones, Ian (2016). “The Politics of Sustainability and Development”. Annual Review of Environment and Resources. 41 (1): 293–319. doi:10.1146/annurev-environ-110615-090039. ISSN 1543-5938. S2CID 156534921.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f g h i Harrington, Lisa M. Butler (2016). “Sustainability Theory and Conceptual Considerations: A Review of Key Ideas for Sustainability, and the Rural Context”. Papers in Applied Geography. 2 (4): 365–382. Bibcode:2016PAGeo…2..365H. doi:10.1080/23754931.2016.1239222. ISSN 2375-4931. S2CID 132458202.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d United Nations General Assembly (1987) Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development: Our Common Future. Transmitted to the General Assembly as an Annex to document A/42/427 – Development and International Co-operation: Environment.

- ^ United Nations General Assembly (20 March 1987). “Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development: Our Common Future; Transmitted to the General Assembly as an Annex to document A/42/427 – Development and International Co-operation: Environment; Our Common Future, Chapter 2: Towards Sustainable Development; Paragraph 1″. United Nations General Assembly. Retrieved 1 March 2010.

- ^ “University of Alberta: What is sustainability?” (PDF). mcgill.ca. Retrieved 13 August 2022.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Halliday, Mike (21 November 2016). “How sustainable is sustainability?”. Oxford College of Procurement and Supply. Retrieved 12 July 2022.

- ^ Harper, Douglas. “sustain”. Online Etymology Dictionary.

- ^ Onions, Charles, T. (ed) (1964). The Shorter Oxford English Dictionary. Oxford: Clarendon Press. p. 2095.

- ^ “Sustainability Theories”. World Ocean Review. Retrieved 20 June 2019.

- ^ Compare: “sustainability”. Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.) The English-language word had a legal technical sense from 1835 and a resource-management connotation from 1953.

- ^ “Hans Carl von Carlowitz and Sustainability”. Environment and Society Portal. Retrieved 20 June 2019.

- ^ Dresden, SLUB. “Sylvicultura Oeconomica, Oder Haußwirthliche Nachricht und Naturmäßige Anweisung Zur Wilden Baum-Zucht”. digital.slub-dresden.de (in German). Retrieved 28 March 2022.

- ^ Von Carlowitz, H.C. & Rohr, V. (1732) Sylvicultura Oeconomica, oder Haußwirthliche Nachricht und Naturmäßige Anweisung zur Wilden Baum Zucht, Leipzig; translated from German as cited in Friederich, Simon; Symons, Jonathan (15 November 2022). “Operationalising sustainability? Why sustainability fails as an investment criterion for safeguarding the future”. Global Policy. 14: 1758–5899.13160. doi:10.1111/1758-5899.13160. ISSN 1758-5880. S2CID 253560289.

- ^ Basler, Ernst (1972). Strategy of Progress: Environmental Pollution, Habitat Scarcity and Future Research (originally, Strategie des Fortschritts: Umweltbelastung Lebensraumverknappung and Zukunftsforshung). BLV Publishing Company.

- ^ Gadgil, M.; Berkes, F. (1991). “Traditional Resource Management Systems”. Resource Management and Optimization. 8: 127–141.

- ^ “Resolution adopted by the General Assembly on 16 September 2005, 60/1. 2005 World Summit Outcome” (PDF). United Nations General Assembly. 2005. Retrieved 17 January 2022.

- ^ Barbier, Edward B. (July 1987). “The Concept of Sustainable Economic Development”. Environmental Conservation. 14 (2): 101–110. Bibcode:1987EnvCo..14..101B. doi:10.1017/S0376892900011449. ISSN 1469-4387.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Bosselmann, K. (2022) Chapter 2: A normative approach to environmental governance: sustainability at the apex of environmental law, Research Handbook on Fundamental Concepts of Environmental Law, edited by Douglas Fisher

- ^ Jump up to:a b “Agenda 21” (PDF). United Nations Conference on Environment & Development, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 3 to 14 June 1992. 1992. Retrieved 17 January 2022.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d United Nations (2015) Resolution adopted by the General Assembly on 25 September 2015, Transforming our world: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (A/RES/70/1 Archived 28 November 2020 at the Wayback Machine)

- ^ Scott Cato, M. (2009). Green Economics. London: Earthscan, pp. 36–37. ISBN 978-1-84407-571-3.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Obrecht, Andreas; Pham-Truffert, Myriam; Spehn, Eva; Payne, Davnah; Altermatt, Florian; Fischer, Manuel; Passarello, Cristian; Moersberger, Hannah; Schelske, Oliver; Guntern, Jodok; Prescott, Graham (5 February 2021). “Achieving the SDGs with Biodiversity”. Swiss Academies Factsheet. Vol. 16, no. 1. doi:10.5281/zenodo.4457298.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f Raskin, P.; Banuri, T.; Gallopín, G.; Gutman, P.; Hammond, A.; Kates, R.; Swart, R. (2002). Great transition: the promise and lure of the times ahead. Boston: Stockholm Environment Institute. ISBN 0-9712418-1-3. OCLC 49987854.

- ^ Ekins, Paul; Zenghelis, Dimitri (2021). “The costs and benefits of environmental sustainability”. Sustainability Science. 16 (3): 949–965. Bibcode:2021SuSc…16..949E. doi:10.1007/s11625-021-00910-5. PMC 7960882. PMID 33747239.

- ^ William L. Thomas, ed. (1956). Man’s role in changing the face of the earth. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-79604-3. OCLC 276231.

- ^ Carson, Rachel (2002) [1st. Pub. Houghton Mifflin, 1962]. Silent Spring. Mariner Books. ISBN 978-0-618-24906-0.

- ^ Arrhenius, Svante (1896). “XXXI. On the influence of carbonic acid in the air upon the temperature of the ground”. The London, Edinburgh, and Dublin Philosophical Magazine and Journal of Science. 41 (251): 237–276. doi:10.1080/14786449608620846. ISSN 1941-5982.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c UN (1973) Report of the United Nations Conference on the Human Environment, A/CONF.48/14/Rev.1, Stockholm, 5–16 June 1972

- ^ UNEP (2021). “Making Peace With Nature”. UNEP – UN Environment Programme. Retrieved 30 March 2022.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d Ripple, William J.; Wolf, Christopher; Newsome, Thomas M.; Galetti, Mauro; Alamgir, Mohammed; Crist, Eileen; Mahmoud, Mahmoud I.; Laurance, William F.; 15,364 scientist signatories from 184 countries (2017). “World Scientists’ Warning to Humanity: A Second Notice”. BioScience. 67 (12): 1026–1028. doi:10.1093/biosci/bix125. hdl:11336/71342. ISSN 0006-3568.

- ^ Crutzen, Paul J. (2002). “Geology of mankind”. Nature. 415 (6867): 23. Bibcode:2002Natur.415…23C. doi:10.1038/415023a. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 11780095. S2CID 9743349.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Wilhelm Krull, ed. (2000). Zukunftsstreit (in German). Weilerwist: Velbrück Wissenschaft. ISBN 3-934730-17-5. OCLC 52639118.

- ^ Redclift, Michael (2005). “Sustainable development (1987-2005): an oxymoron comes of age”. Sustainable Development. 13 (4): 212–227. doi:10.1002/sd.281. ISSN 0968-0802.

- ^ Daly, Herman E. (1996). Beyond growth: the economics of sustainable development (PDF). Boston: Beacon Press. ISBN 0-8070-4708-2. OCLC 33946953.

- ^ United Nations (2017) Resolution adopted by the General Assembly on 6 July 2017, Work of the Statistical Commission pertaining to the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (A/RES/71/313)

- ^ “UN Environment | UNDP-UN Environment Poverty-Environment Initiative”. UN Environment | UNDP-UN Environment Poverty-Environment Initiative. Retrieved 24 January 2022.

- ^ PEP (2016) Poverty-Environment Partnership Joint Paper | June 2016 Getting to Zero – A Poverty, Environment and Climate Call to Action for the Sustainable Development Goals

- ^ Boyer, Robert H. W.; Peterson, Nicole D.; Arora, Poonam; Caldwell, Kevin (2016). “Five Approaches to Social Sustainability and an Integrated Way Forward”. Sustainability. 8 (9): 878. doi:10.3390/su8090878.

- ^ Doğu, Feriha Urfalı; Aras, Lerzan (2019). “Measuring Social Sustainability with the Developed MCSA Model: Güzelyurt Case”. Sustainability. 11 (9): 2503. doi:10.3390/su11092503. ISSN 2071-1050.

- ^ Davidson, Mark (2010). “Social Sustainability and the City: Social sustainability and city”. Geography Compass. 4 (7): 872–880. doi:10.1111/j.1749-8198.2010.00339.x.

- ^ Missimer, Merlina; Robèrt, Karl-Henrik; Broman, Göran (2017). “A strategic approach to social sustainability – Part 2: a principle-based definition”. Journal of Cleaner Production. 140: 42–52. Bibcode:2017JCPro.140…42M. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.04.059.

- ^ Boyer, Robert; Peterson, Nicole; Arora, Poonam; Caldwell, Kevin (2016). “Five Approaches to Social Sustainability and an Integrated Way Forward”. Sustainability. 8 (9): 878. doi:10.3390/su8090878. ISSN 2071-1050.

- ^ James, Paul; with Magee, Liam; Scerri, Andy; Steger, Manfred B. (2015). Urban Sustainability in Theory and Practice: Circles of Sustainability. London: Routledge. ISBN 9781315765747.

- ^ Liam Magee; Andy Scerri; Paul James; James A. Thom; Lin Padgham; Sarah Hickmott; Hepu Deng; Felicity Cahill (2013). “Reframing social sustainability reporting: Towards an engaged approach”. Environment, Development and Sustainability. 15 (1): 225–243. Bibcode:2013EDSus..15..225M. doi:10.1007/s10668-012-9384-2. S2CID 153452740.

- ^ Cohen, J. E. (2006). “Human Population: The Next Half Century.”. In Kennedy, D. (ed.). Science Magazine’s State of the Planet 2006-7. London: Island Press. pp. 13–21. ISBN 9781597266246.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Aggarwal, Dhruvak; Esquivel, Nhilce; Hocquet, Robin; Martin, Kristiina; Mungo, Carol; Nazareth, Anisha; Nikam, Jaee; Odenyo, Javan; Ravindran, Bhuvan; Kurinji, L. S.; Shawoo, Zoha; Yamada, Kohei (28 April 2022). Charting a youth vision for a just and sustainable future (PDF) (Report). Stockholm Environment Institute. doi:10.51414/sei2022.010.

- ^ “The Regional Institute – WACOSS Housing and Sustainable Communities Indicators Project”. www.regional.org.au. 2012. Retrieved 26 January 2022.

- ^ Virtanen, Pirjo Kristiina; Siragusa, Laura; Guttorm, Hanna (2020). “Introduction: toward more inclusive definitions of sustainability”. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability. 43: 77–82. Bibcode:2020COES…43…77V. doi:10.1016/j.cosust.2020.04.003. S2CID 219663803.

- ^ “Culture: Fourth Pillar of Sustainable Development”. United Cities and Local Governments. Archived from the original on 3 October 2013.

- ^ James, Paul; Magee, Liam (2016). “Domains of Sustainability”. In Farazmand, Ali (ed.). Global Encyclopedia of Public Administration, Public Policy, and Governance. Cham: Springer International Publishing. pp. 1–17. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-31816-5_2760-1. ISBN 978-3-319-31816-5. Retrieved 28 March 2022.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Robert U. Ayres & Jeroen C.J.M. van den Bergh & John M. Gowdy, 1998. “Viewpoint: Weak versus Strong Sustainability“, Tinbergen Institute Discussion Papers 98-103/3, Tinbergen Institute.

- ^ Pearce, David W.; Atkinson, Giles D. (1993). “Capital theory and the measurement of sustainable development: an indicator of “weak” sustainability”. Ecological Economics. 8 (2): 103–108. Bibcode:1993EcoEc…8..103P. doi:10.1016/0921-8009(93)90039-9.

- ^ Ayres, Robert; van den Berrgh, Jeroen; Gowdy, John (2001). “Strong versus Weak Sustainability”. Environmental Ethics. 23 (2): 155–168. doi:10.5840/enviroethics200123225. ISSN 0163-4275.

- ^ Cabeza Gutés, Maite (1996). “The concept of weak sustainability”. Ecological Economics. 17 (3): 147–156. Bibcode:1996EcoEc..17..147C. doi:10.1016/S0921-8009(96)80003-6.

- ^ Bosselmann, Klaus (2017). The principle of sustainability: transforming law and governance (2nd ed.). London: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-4724-8128-3. OCLC 951915998.

- ^ Jump up to:a b WEF (2020) Nature Risk Rising: Why the Crisis Engulfing Nature Matters for Business and the Economy New Nature Economy, World Economic Forum in collaboration with PwC

- ^ James, Paul; with Magee, Liam; Scerri, Andy; Steger, Manfred B. (2015). Urban Sustainability in Theory and Practice: Circles of Sustainability. London: Routledge. ISBN 9781315765747.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Hardyment, Richard (2 February 2024). Measuring Good Business. London: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9781003457732. ISBN 978-1-003-45773-2.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Bell, Simon and Morse, Stephen 2008. Sustainability Indicators. Measuring the Immeasurable? 2nd edn. London: Earthscan. ISBN 978-1-84407-299-6.

- ^ Dalal-Clayton, Barry and Sadler, Barry 2009. Sustainability Appraisal: A Sourcebook and Reference Guide to International Experience. London: Earthscan. ISBN 978-1-84407-357-3.[page needed]

- ^ Hak, T. et al. 2007. Sustainability Indicators, SCOPE 67. Island Press, London. [1] Archived 2011-12-18 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Wackernagel, Mathis; Lin, David; Evans, Mikel; Hanscom, Laurel; Raven, Peter (2019). “Defying the Footprint Oracle: Implications of Country Resource Trends”. Sustainability. 11 (7): 2164. doi:10.3390/su11072164.

- ^ “Sustainable Development visualized”. Sustainability concepts. Retrieved 24 March 2022.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Steffen, Will; Rockström, Johan; Cornell, Sarah; Fetzer, Ingo; Biggs, Oonsie; Folke, Carl; Reyers, Belinda (15 January 2015). “Planetary Boundaries – an update”. Stockholm Resilience Centre. Retrieved 19 April 2020.

- ^ “Ten years of nine planetary boundaries”. Stockholm Resilience Centre. November 2019. Retrieved 19 April 2020.

- ^ Persson, Linn; Carney Almroth, Bethanie M.; Collins, Christopher D.; Cornell, Sarah; de Wit, Cynthia A.; Diamond, Miriam L.; Fantke, Peter; Hassellöv, Martin; MacLeod, Matthew; Ryberg, Morten W.; Søgaard Jørgensen, Peter (1 February 2022). “Outside the Safe Operating Space of the Planetary Boundary for Novel Entities”. Environmental Science & Technology. 56 (3): 1510–1521. Bibcode:2022EnST…56.1510P. doi:10.1021/acs.est.1c04158. ISSN 0013-936X. PMC 8811958. PMID 35038861.

- ^ Ehrlich, P.R.; Holden, J.P. (1974). “Human Population and the global environment”. American Scientist. Vol. 62, no. 3. pp. 282–292.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d Wiedmann, Thomas; Lenzen, Manfred; Keyßer, Lorenz T.; Steinberger, Julia K. (2020). “Scientists’ warning on affluence”. Nature Communications. 11 (1): 3107. Bibcode:2020NatCo..11.3107W. doi:10.1038/s41467-020-16941-y. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 7305220. PMID 32561753. Text was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

- ^ Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (2005). Ecosystems and Human Well-being: Biodiversity Synthesis (PDF). Washington, DC: World Resources Institute.

- ^ TEEB (2010), The Economics of Ecosystems and Biodiversity: Mainstreaming the Economics of Nature: A Synthesis of the Approach, Conclusions and Recommendations of TEEB

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Jaeger, William K. (2005). Environmental economics for tree huggers and other skeptics. Washington, DC: Island Press. ISBN 978-1-4416-0111-7. OCLC 232157655.

- ^ Groth, Christian (2014). Lecture notes in Economic Growth, (mimeo), Chapter 8: Choice of social discount rate. Copenhagen University.

- ^ UNEP, FAO (2020). UN Decade on Ecosystem Restoration. 48p.

- ^ Raworth, Kate (2017). Doughnut economics: seven ways to think like a 21st-century economist. London: Random House. ISBN 978-1-84794-138-1. OCLC 974194745.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e Berg, Christian (2017). “Shaping the Future Sustainably – Types of Barriers and Tentative Action Principles (chapter in: Future Scenarios of Global Cooperation—Practices and Challenges)”. Global Dialogues (14). Centre For Global Cooperation Research (KHK/GCR21), Nora Dahlhaus and Daniela Weißkopf (eds.). doi:10.14282/2198-0403-GD-14. ISSN 2198-0403.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d Pickering, Jonathan; Hickmann, Thomas; Bäckstrand, Karin; Kalfagianni, Agni; Bloomfield, Michael; Mert, Ayşem; Ransan-Cooper, Hedda; Lo, Alex Y. (2022). “Democratising sustainability transformations: Assessing the transformative potential of democratic practices in environmental governance”. Earth System Governance. 11: 100131. Bibcode:2022ESGov..1100131P. doi:10.1016/j.esg.2021.100131. Text was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

- ^ European Environment Agency. (2019). Sustainability transitions: policy and practice. LU: Publications Office. doi:10.2800/641030. ISBN 9789294800862.

- ^ Noura Guimarães, Lucas (2020). “Introduction”. The regulation and policy of Latin American energy transitions. Elsevier. pp. xxix–xxxviii. doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-819521-5.00026-7. ISBN 978-0-12-819521-5. S2CID 241093198.

- ^ Kuenkel, Petra (2019). Stewarding Sustainability Transformations: An Emerging Theory and Practice of SDG Implementation. Cham: Springer. ISBN 978-3-030-03691-1. OCLC 1080190654.

- ^ Fletcher, Charles; Ripple, William J.; Newsome, Thomas; Barnard, Phoebe; Beamer, Kamanamaikalani; Behl, Aishwarya; Bowen, Jay; Cooney, Michael; Crist, Eileen; Field, Christopher; Hiser, Krista; Karl, David M.; King, David A.; Mann, Michael E.; McGregor, Davianna P.; Mora, Camilo; Oreskes, Naomi; Wilson, Michael (4 April 2024). “Earth at risk: An urgent call to end the age of destruction and forge a just and sustainable future”. PNAS Nexus. 3 (4): pgae106. doi:10.1093/pnasnexus/pgae106. PMC 10986754. PMID 38566756. Retrieved 4 April 2024. Text was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

- ^ Smith, E. T. (23 January 2024). “Practising Commoning”. The Commons Social Change Library. Retrieved 23 February 2024.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Haberl, Helmut; Wiedenhofer, Dominik; Virág, Doris; Kalt, Gerald; Plank, Barbara; Brockway, Paul; Fishman, Tomer; Hausknost, Daniel; Krausmann, Fridolin; Leon-Gruchalski, Bartholomäus; Mayer, Andreas (2020). “A systematic review of the evidence on decoupling of GDP, resource use and GHG emissions, part II: synthesizing the insights”. Environmental Research Letters. 15 (6): 065003. Bibcode:2020ERL….15f5003H. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/ab842a. ISSN 1748-9326. S2CID 216453887.

- ^ Pigou, Arthur Cecil (1932). The Economics of Welfare (PDF) (4th ed.). London: Macmillan.

- ^ Jaeger, William K. (2005). Environmental economics for tree huggers and other skeptics. Washington, DC: Island Press. ISBN 978-1-4416-0111-7. OCLC 232157655.

- ^ Roger Perman; Yue Ma; Michael Common; David Maddison; James Mcgilvray (2011). Natural resource and environmental economics (4th ed.). Harlow, Essex: Pearson Addison Wesley. ISBN 978-0-321-41753-4. OCLC 704557307.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Anderies, John M.; Janssen, Marco A. (16 October 2012). “Elinor Ostrom (1933–2012): Pioneer in the Interdisciplinary Science of Coupled Social-Ecological Systems”. PLOS Biology. 10 (10): e1001405. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1001405. ISSN 1544-9173. PMC 3473022.

- ^ “The Nobel Prize: Women Who Changed the World”. thenobelprize.org. Retrieved 31 March 2022.

- ^ Ghisellini, Patrizia; Cialani, Catia; Ulgiati, Sergio (15 February 2016). “A review on circular economy: the expected transition to a balanced interplay of environmental and economic systems”. Journal of Cleaner Production. Towards Post Fossil Carbon Societies: Regenerative and Preventative Eco-Industrial Development. 114: 11–32. Bibcode:2016JCPro.114…11G. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2015.09.007. ISSN 0959-6526.

- ^ Nobre, Gustavo Cattelan; Tavares, Elaine (10 September 2021). “The quest for a circular economy final definition: A scientific perspective”. Journal of Cleaner Production. 314: 127973. Bibcode:2021JCPro.31427973N. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.127973. ISSN 0959-6526.

- ^ Zhexembayeva, N. (May 2007). “Becoming Sustainable: Tools and Resources for Successful Organizational Transformation”. Center for Business as an Agent of World Benefit. Case Western University. Archived from the original on 13 June 2010.

- ^ “About Us”. Sustainable Business Institute. Archived from the original on 17 May 2009.

- ^ “About the WBCSD”. World Business Council for Sustainable Development (WBCSD). Archived from the original on 9 September 2007. Retrieved 1 April 2009.

- ^ “Supply Chain Sustainability | UN Global Compact”. www.unglobalcompact.org. Retrieved 4 May 2022.

- ^ “”Statement of Faith and Spiritual Leaders on the upcoming United Nations Climate Change Conference, COP21 in Paris in December 2015″” (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 December 2015. Retrieved 21 March 2022.

- ^ “The Statement — Interfaith Climate”. www.interfaithclimate.org. Retrieved 13 August 2022.

- ^ McDilda, Diane Gow (2007). The everything green living book: easy ways to conserve energy, protect your family’s health, and help save the environment. Avon, Mass.: Adams Media. ISBN 978-1-59869-425-3. OCLC 124074971.

- ^ Gambino, Megan (15 March 2012). “Is it Too Late for Sustainable Development?”. Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved 12 January 2022.

- ^ Blühdorn (2017). “Post-capitalism, post-growth, post-consumerism? Eco-political hopes beyond sustainability”. Global Discourse. 7 (1): 42–61. doi:10.1080/23269995.2017.1300415. ISSN 2043-7897.

- ^ Watson, Bruce (20 August 2016). “The troubling evolution of corporate greenwashing”. The Guardian. Archived from the original on 18 October 2016.

- ^ “The Troubling Evolution Of Large Scale Corporate Greenwashing”. www.bloomberg.ca. BNN Bloomberg. 18 August 2018.

- ^ “The Troubling Evolution Of Large Scale Corporate Greenwashing”. The Conversation. 18 August 2011.

- ^ Ebrahimi Sirizi, Mohammad; Taghavi Zirvani, Esmaeil; Esmailzadeh, Abdulsalam; Khosravian, Jafar; Ahmadi, Reyhaneh; Mijani, Naeim; Soltannia, Reyhaneh; Jokar Arsanjani, Jamal (19 October 2023). “A scenario-based multi-criteria decision-making approach for allocation of pistachio processing facilities: A case study of Zarand, Iran”. Sustainability. 15 (20): 15054. doi:10.3390/su152015054. ISSN 2071-1050.